1816-1882: THE STETHOSCOPE

The stethoscope was invented in 1816 when a young French physician named René Théophile-Hyacinthe Laennec was examining a 40 year old female patient named Marie-Melanie Basset who had shortness of breath. Laennec was embarrassed to place his ear to her chest and perform immediate auscultation, which was the method of auscultation used by physicians at that time. He remembered a trick he learned as a child about how sound travels through solids. He rolled up 24 sheets of paper, placed one end to his ear and the other end to the woman’s chest. He was delighted to discover that the sounds were not only conveyed through the paper cone, but they were also loud and clear. He named this process mediate auscultation.

Portrait of René Théophile-Hyacinthe Laennec, circa 1820s, courtesy of U.S. National Library of Medicine in the public domain. FROM: https://ihm.nlm.nih.gov/luna/servlet/detail/NLMNLM~1~1~101420941~182508:Laennec?sort=title%2Csubject_mesh_term%2Ccreator_person%2Ccreator_organization&qvq=q:laennec;sort:title%2Csubject_mesh_term%2Ccreator_person%2Ccreator_organization&mi=3&trs=13

Laennec preferred to have his instrument simply called Le Cylindre, as he thought naming such a fundamental instrument was unnecessary. He did not approve of the names his colleagues had given the instrument, and decided that if it should be called anything, it should be called the stethoscope. The word stethoscope is derived from the Greek word stethos meaning chest and scope, a French word derived from the Latin scopium meaning ‘a viewing instrument’.

One of Laennec’s original stethoscopes made from wood and brass. Courtesy of the Science Museum of London

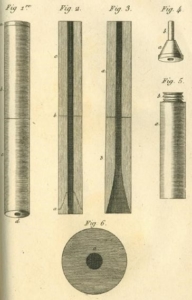

Laennec was a skilled woodturner; he had set up a small shop in his home with a woodturning lathe and stocked different types of wood. He created a stethoscope from a turned piece of wood with a hollow bore in the center. It was made of two pieces: one end had a hole to place against the ear, and the other end was hollowed out into a funnel shaped cone; there was a plug that fit into this cone, which had a hollow brass tube placed inside it in order to listen to the heart. The stethoscope could be used without the tube to examine the lungs. The stethoscope was described as being 12 inches long and 1.5 inches in diameter with a 3/8 inch central bore hole throughout its length. His stethoscope could be bought for 2 francs along with the purchase of the Treatise on Mediate Auscultation.

Laennec published his classic Treatise on Mediate Auscultation in 1819 in which he discussed mediate auscultation and illustrated his design of the stethoscope. A second edition was published in 1826, just after Laennec died from Tuberculosis: one of the diseases he spent long hours studying with the aid of his stethoscope.

Laennec was the first to describe the auscultatory signs we still use in medicine today, such as ‘bruit,’ ‘rales,’ bronchophony,’ and ‘egophony.’ He was also well known for his work on cirrhosis, which is

still referred to as “Laennec’s cirrhosis.” The stethoscope allowed him to extensively study chest diseases and especially tuberculosis.

In his book, Laennec tells how he went through several experiments to get from the rolled up paper to the hollow wooden cylinder. He also gives the reader strict guidelines on how a proper stethoscope is to be constructed, as well as used.

This first version of the stethoscope is illustrated in Laennec’s first edition text on auscultation. Laennec turned the first stethoscopes himself and these were somewhat longer than described in his text. Image is in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Laennec examining a tuberculous patient by immediate auscultation with the unaided ear in the Necker Hospital, Paris, France. In his left hand is the stethoscope that he used for mediate auscultation. Image in the public domain, courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

A second version of the Laennec stethoscope was made circa 1826 and illustrated in the second edition of Laennec’s text on auscultation. The cylindrical stethoscope has three parts fitting together: rounded wood pressure fittings, brass tube fitting, and horn rings at the juncture of the three parts.

A unique second version of the circa 1826 Laennec stethoscope with extension piece for fetal auscultation.

A variant of the Laennec stethoscope was made of cedar wood with an extension piece made of cedar, ivory, and horn circa 1826. The stethoscope and its extension pieces can be taken apart. The extension screws into the chest plug, which allows fetal auscultation via the vagina.

This stethoscope is the so-called third version of the Laennec stethoscope. A close up of the maker’s mark in shown on the right.

A third version of Laennec’s stethoscope was most likely developed in England. It is marked Weiss, London, under a Crown and GR, which stands for George Rex (King George IV) who reigned from 1820-1830, thus clearly dating this stethoscope to that period. The only other known example with this mark is in the Wellcome Medical Museum, London. In this version, a brass tube is no longer used to hold the chest plug in place, and the parts of the stethoscope are attached by a funnel shaped, wood pressure fitting.

Examples of one-piece stethoscopes manufactured circa 1830; a pediatric version is on the left and an adult version is on the right.

The stethoscope was not embraced immediately, but it eventually became recognized by physicians as a valuable instrument for physical diagnosis. There were several improvements to Laennec’s stethoscope over the years, the most notable was that of Pierre Adolphe Piorry in 1828. Piorry incorporated another diagnostic instrument, known as a “pleximeter” into his stethoscope

Portrait of Pierre Adolphe Piorry, circa 1830s. Image is in the public domain, courtesy of the National Library of Medicine

Original Piorry stethoscope made of wood and ivory, circa 1828. This is the stethoscope illustrated in Piorry’s text on percussion published in 1828.

The Piorry stethoscope evolved to have a thinner stem without an extension piece and was about half the size of Laennec’s. It was trumpet shaped, made of wood, and had a removable wood plug, ivory earpiece and chest piece. The ivory chest piece also served as a pleximeter. It could be used with or without the extension piece attached. Most stethoscopes made after 1830 were modeled after the Piorry design. The Piorry stethoscope was also the inspiration for Sir Oliver Wendell Holmes to write his “STETHOSCOPE SONG,” which was published in 1848.

Piorry Stethoscope made of cedar and ivory with percussion hammer with its case, circa 1835.

Later model Piorry stethoscope made from ebony. The stethoscope is taken apart showing the ivory pleximeter with finger grasps and a smaller ivory ear plate, circa 1840.

A rare and wonderful example of medical scrimshaw is shown on this presentation Piorry stethoscope. The stethoscope is assembled for auscultation on the right. The scrimshaw is shown on the left. The ivory pleximeter which screws onto the funnel shaped chest end has a etching of a thumb lancet used for bloodletting, poppy seed used to make morphine, and Asclepius’s staff showing a rod and snake (the medical caduceus), and in latin the words Conjurat and Amice (from your wife with love). The ivory ear plate which screws onto the stem reveals the presentation date: May/11/1829, and Paris etched on the inner surface.

A stethoscope, circa 1830, that combines the characteristics of the Laennec (chest plug with brass tube) and Piorry (chest bell and ivory earpiece) stethoscopes.

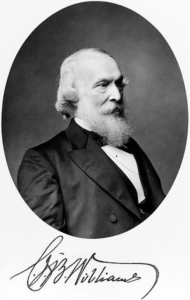

Portrait of Charles James Blasius Williams, image is in the public domain courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Charles James Blasius Williams developed another approach to the design of the stethoscope. He introduced a two-piece monaural stethoscope in 1843 with a trumpet shaped chest end that fit more comfortably and snugly against the chest wall. His stethoscope had a removable ear piece.

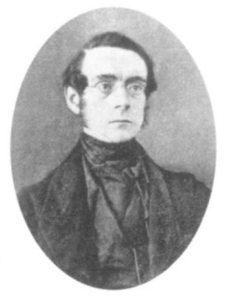

Portrait of Golding Bird, published in his obituary circa 1855. Imagine is in the public domain courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

The next innovation in stethoscope was the introduction of a flexible binaural stethoscope with articulated joints, which was first described in 1829 but expanded upon by Golding Bird, a British physician, in 1840 where he described a stethoscope with a flexible tube. While he was the first to publish documentation on flexible stethoscopes, he noted that earlier designs existed and described them as “snake ear trumpets.” However, Bird’s stethoscope only had a single earpiece, and it was not until 1851 when Arthur Leared, an Irish physician, invented the binaural stethoscope.

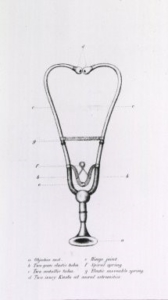

George Cammann’s binaural stethoscope circa 1855, image is in the public domain courtesy of the National Library of Medicine.

The binaural stethoscope was further improved upon in 1852 by George Cammann, a New York City, NY physician. Cammann’s improvements allowed the stethoscope to be produced commercially; he also wrote a treatise on diagnosis by auscultation, which was only possible with the newer, refined stethoscope.

By 1873, there were descriptions of a differential stethoscope that could connect to slightly different locations to create a slight stereo effect, though this did not become a standard tool in clinical practice.

Stethoscopes were often carried in a medical bag when the doctor was making a house call on a patient; but such medical bags called attention to the physician, and the possibility that he may be carrying drugs including opiates that were commonly used as medication in the 19th century. Medical canes were a method for carrying drugs in a form that would not reveal the identity of the physician.

This is the only known medical cane that incorporates a stethoscope in the body of the cane. It was presented to Dr. Robert Parsons by Dr. Richard Sanford Hallock of Salida, Colorado in August 1882.

The rare and unique medical cane pictured above was made of hard rubber with a removable metal assembly that holds fourteen original, cork-stopped medicine vials. The vials have their original label and contents. By removing the lower tube of the cane and attaching a bell and earpiece from the handle, a seventeen inch stethoscope is assembled. The brass presentation ring just below the handle is inscribed: From Dr. Parsons to Dr. Hallock Aug. 1882.

Submitted to NEMSM May 2007, author unknown, additional content by NEMSM Volunteers